The year 1939 saw two events that would have stood out in importance in O’Flaherty’s mind. In March, Cardinal Pacelli was crowned Pope Pius XII. And in September, World War Two began.

The year 1939 saw two events that would have stood out in importance in O’Flaherty’s mind. In March, Cardinal Pacelli was crowned Pope Pius XII. And in September, World War Two began. The Nazis invaded Poland. Britain and France declared war on Germany in return. Ireland remained neutral—with an army of only seven thousand men, and a navy that consisted of two ships, its position was extremely precarious. But Italy’s Fascist leader, Benito Mussolini, was confident of his own country’s strength. He had signed a “Pact of Steel” with Adolf Hitler; once Germany went to war, Italy was bound to follow.

On June 10, 1940, Italy declared war on France and Britain. O’Flaherty, doubly neutral as an Irishman and a priest, found himself in the middle of a war zone. But he was in the middle of it in a very special way.

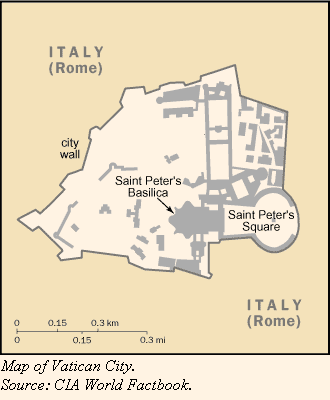

The Vatican City, where O’Flaherty lived and worked, is the spiritual and physical capital of the Roman Catholic Church. It traces back to the fourth century A.D., when a basilica was built to honor the tomb of the Apostle Peter. During the 1300’s, the popes began to take up residence in palaces around the basilica. Vatican City became the seat of the Holy See, the central government of the Catholic Church.

The Vatican City, where O’Flaherty lived and worked, is the spiritual and physical capital of the Roman Catholic Church. It traces back to the fourth century A.D., when a basilica was built to honor the tomb of the Apostle Peter. During the 1300’s, the popes began to take up residence in palaces around the basilica. Vatican City became the seat of the Holy See, the central government of the Catholic Church. The pope originally ruled the Vatican like a monarch. But as the various Italian cities and states unified into the country of Italy during the 1860’s and ‘70’s, the question arose: who would have control over Vatican City, the pope or the new Italian government? And if the pope is to be the spiritual leader of a worldwide body, what should be his relationship to secular governments?

These questions had only been settled within O’Flaherty’s lifetime. In 1929, Mussolini and Cardinal Gasparri signed the Lateran Treaty, which recognized the “absolute and visible independence” of the pope and gave him “sovereign jurisdiction” over Vatican City and a few other properties owned by the Church. The Vatican would become an independent country, with its own laws, its own money, and its own court system. It would not be subject to Italian regulations or taxes. In return, the Holy See promised not to get involved in the politics of Italy, and to maintain absolute neutrality in all international affairs. This treaty was only a decade old at the outbreak of World War Two.

When Italy went to war in 1940, the Vatican was effectively isolated in Fascist territory. In this position, it was vulnerable to the decisions of Mussolini and Hitler, but it was equally as vulnerable to British and American bombing raids. Halfway through the war, the Germans had a white line painted on the cobbles across the opening of St. Peter’s Square. This was ostensibly to keep Axis troops out and show them where their jurisdiction ended—but some also saw it as a way to keep Vatican members in, and show them where their neutral privileges ended. Whatever the case, it was a very literal expression of the figurative fine line the Vatican’s citizens had to walk during the war.