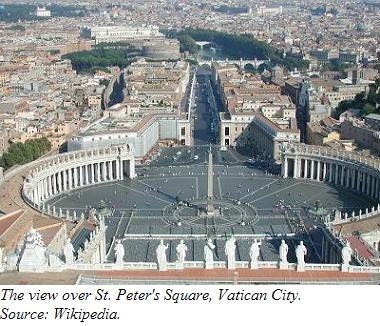

Of course, O’Flaherty’s organization was not the only one hiding and aiding refugees in Rome. But as William Norman Grigg writes in The New American, “What distinguished O'Flaherty from his colleagues was his audacity.” Almost every evening, O’Flaherty would stand on the top step of St. Peter’s, in full view of the SS troops patrolling the white boundary line. He was saying his prayers, but he was also waiting for anyone in need to approach him. He had numerous tricks for smuggling people in or out of the Vatican. Sometimes he disguised them in his own monsignorial robes. One young lady was dressed up in a Swiss Guard uniform and marched right through. O’Flaherty himself moved pretty openly through Rome, calling on friends, collaborators and supporters, collecting money or supplies, visiting hospitals and the notorious Regina Coeli prison. “He used to play games with the Germans,” recounted one of the rescued POWs, Major William Simpson, in his book, A Vatican Lifeline. “It was the most gigantic game of hide-and-seek you've ever seen.”

Of course, O’Flaherty’s organization was not the only one hiding and aiding refugees in Rome. But as William Norman Grigg writes in The New American, “What distinguished O'Flaherty from his colleagues was his audacity.” Almost every evening, O’Flaherty would stand on the top step of St. Peter’s, in full view of the SS troops patrolling the white boundary line. He was saying his prayers, but he was also waiting for anyone in need to approach him. He had numerous tricks for smuggling people in or out of the Vatican. Sometimes he disguised them in his own monsignorial robes. One young lady was dressed up in a Swiss Guard uniform and marched right through. O’Flaherty himself moved pretty openly through Rome, calling on friends, collaborators and supporters, collecting money or supplies, visiting hospitals and the notorious Regina Coeli prison. “He used to play games with the Germans,” recounted one of the rescued POWs, Major William Simpson, in his book, A Vatican Lifeline. “It was the most gigantic game of hide-and-seek you've ever seen.” O’Flaherty was actually a fairly distinctive figure, given his height, his glasses, and the wide-brimmed hat and red-and-black cassock he wore as a monsignor. But he was not above disguising himself. Sometimes he would put on the uniform of a postman or a street cleaner; other times, he would go out in the clothes of a simple laborer. There is even a story that he occasionally dressed up as a nun. For years before the war, O’Flaherty had made a habit of saying a very early Sunday morning mass, which was largely attended by the men who ran Rome’s trolley-system, since their schedule prevented them from going to other services. The friendship and gratitude of these trolley men turned out to be extremely helpful, later, when O’Flaherty needed to move himself and his refugees around Rome.

O’Flaherty was almost never intimidated by his task, and almost always optimistic. One evening, a Jewish couple approached him on the steps of St. Peter’s. They expected to be deported any day, and were resigned to their fate. They asked only that O’Flaherty save their seven-year-old son, and offered the priest a long, solid gold chain in payment. O’Flaherty took the chain, hid the boy safely, and obtained forged identity papers for the couple that allowed them to survive the occupation. At the end of the war, O’Flaherty reunited the parents with their son—and their gold chain. He had kept it in a desk-drawer in his room the entire time. When appalled colleagues asked him why he was being so careless with something so valuable, O’Flaherty shrugged: “Nobody here will steal it.”

Everything O’Flaherty did seemed to have a certain style to it. Once, a man he had hidden in Urban College developed appendicitis. O’Flaherty borrowed a car from an important Vatican official and drove the man to Santo Spirito Hospital, where it was arranged that the nuns would quietly add the man to the surgery list. He was operated on by a German military surgeon, recovered in a ward full of German officers, and was taken back to the College by O’Flaherty.

It was probably this attitude of O’Flaherty’s that made Colonel Kappler so determined to catch the Irishman. The SS had strong suspicions of his activities. But because O’Flaherty was protected by Vatican neutrality, they couldn’t simply arrest and interrogate him; they needed solid proof. Kappler also needed to catch the priest outside that white line. One day it looked as though he had succeeded.

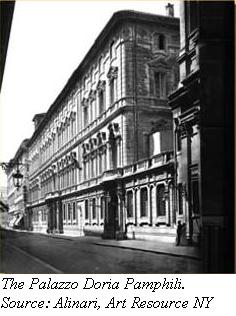

It was probably this attitude of O’Flaherty’s that made Colonel Kappler so determined to catch the Irishman. The SS had strong suspicions of his activities. But because O’Flaherty was protected by Vatican neutrality, they couldn’t simply arrest and interrogate him; they needed solid proof. Kappler also needed to catch the priest outside that white line. One day it looked as though he had succeeded. One of O’Flaherty’s aristocratic friends, Prince Filipo Doria Pamphili, had been supporting the organization with donations of cash. This morning, O’Flaherty had come to pick up the money. But Kappler had the Palazzo Doria under surveillance. Just as O’Flaherty was about to leave, the Prince’s secretary happened to look out the window. The street had been blocked off, SS troops were surrounding the Palazzo, and Kappler himself was getting out of his car to supervise the search. This was it, Prince Filipo said. Time to give up. O’Flaherty didn’t agree. If he could just get himself and the money safely out of the Palazzo, the Germans would have no proof, Prince Filipo wouldn’t be compromised, and everything could keep going.

So as the SS men thundered into the Palazzo, O’Flaherty dived down into the cellars. The act gained him a few moments to think. He noticed a strange rumbling noise. One of the cellars had a chute that opened onto the courtyard above. At the moment, coal was being poured down the chute. O’Flaherty risked a look. Two coalmen were worriedly watching the SS men. O’Flaherty snuck an empty coal sack down into the cellar, pulled off his robe and hat, stuffed them into the sack, and covered his shirt and face with coal dust.

Then he waited until one of the coalmen was right above the chute. O’Flaherty warned him in a whisper, and asked him to hide in the chute while the priest took his place. The man agreed and a few minutes later, O’Flaherty was carrying his sack past two lines of SS men. They moved out of his way so he didn’t get their uniforms dirty. Once the coal truck blocked him from view, he took off down the street.

The coalmen finished their delivery and left, unmolested, while the search moved to the roof. O’Flaherty ducked into the nearest church, washed up in the vestry and resumed his hat and robe. Then he walked unchallenged back to the Vatican. Colonel Kappler spent two hours at the Palazzo Doria, but was forced to leave empty-handed—and very angry.