The Fearful Days.

As Christmas 1943 approached, Major Simpson remembered seeing O’Flaherty’s room “crammed with small parcels, all wrapped in gaily colored paper and tied with red silk ribbons.” Molly Stanley had prepared these packages for the refugees, and O’Flaherty was rallying his fellow priests to help deliver them. The escapees and their hosts were likewise determined that Christmas would be as merry as they could make it. Mrs. Chevalier cooked an epic feast. Delia Murphy gave many impromptu concerts. But on December 27, the “fearful days” began.

As Christmas 1943 approached, Major Simpson remembered seeing O’Flaherty’s room “crammed with small parcels, all wrapped in gaily colored paper and tied with red silk ribbons.” Molly Stanley had prepared these packages for the refugees, and O’Flaherty was rallying his fellow priests to help deliver them. The escapees and their hosts were likewise determined that Christmas would be as merry as they could make it. Mrs. Chevalier cooked an epic feast. Delia Murphy gave many impromptu concerts. But on December 27, the “fearful days” began.

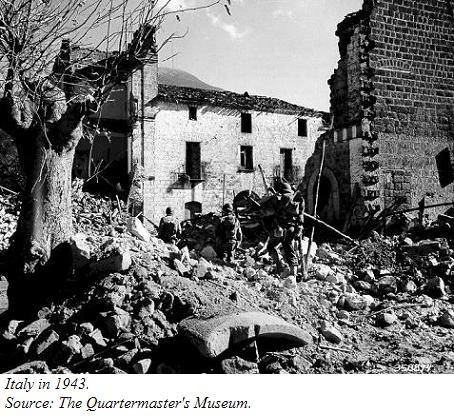

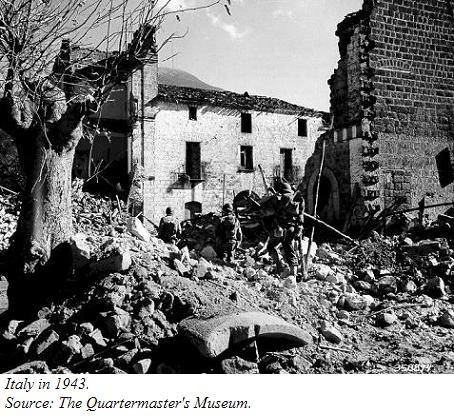

The 7 p.m. curfew was strictly enforced, meaning that the organization had to move refugees around in broad daylight. The easiest gate into the Vatican was sealed off, forcing all visitors to pass through a heavily guarded checkpoint. Food was scarce and the rationing system in chaos. Sometimes the water was shut off, sometimes the electricity. The Allies landed at Anzio in January, but in Rome, it was Kappler who seemed to be winning.

First he arrested 18 Italian padrones. Then he found a young woman involved in the organization and threatened the life of her small child until she agreed to betray several key members. Kappler had SS men pose as escapers on several occasions. Once led to the hideouts and introduced to the padrones, the SS men would pull out guns and place everybody under arrest. From the people captured, Kappler would learn clues that would lead to another raid, on another billet, and more arrests. Each time something like this happened, O’Flaherty and Derry had to abandon the hideouts that had been raided and relocate many of the escapers—always risky. Bruno Buchner, a Yugoslav who had been aiding O’Flaherty since the beginning, was captured, tortured, and having divulged nothing, finally shot. Mrs. Chevalier’s oldest daughter, Gemma, attracted the attention of a plainclothes member of Koch’s police squad one afternoon, and only escaped him by jumping straight across the path of an oncoming trolley. Yet no matter how many people Kappler threatened, arrested, or tortured, he never seemed to get close to O’Flaherty.

Desperate Measures.

By March 1944, Kappler was desperate and frustrated. He ordered two plainclothes SS men to attend Mass at St. Peter’s. At the end of the service, they were to grab O’Flaherty from his post on the basilica steps, and hustle him across the white line, where he would be “shot while escaping.” But John May knew someone who knew someone in the Gestapo’s clerical office, and so got tipped off about the plot. At first, May begged O’Flaherty to disappear for a while. The Monsignor was disinclined: “What, me boy and let them think I am afraid? As long as they don’t use guns I can tackle any two or three of them with ease”.

So May made other plans. As Mass ended, the SS men were tapped on the shoulder by four Swiss Guards and firmly escorted past O’Flaherty. Outside, May had arranged for them to run into a group of Yugoslavian refugees who strongly resented what Hitler had done to their homeland. Gallagher writes, “it was a very bruised and battered pair” of SS men who reported failure to Kappler.

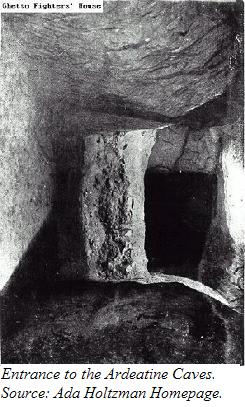

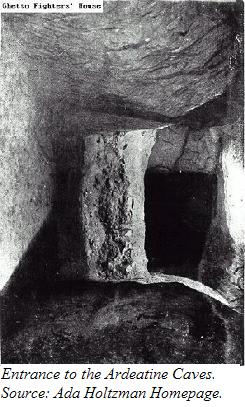

March also saw the massacre at the Ardeatine Caves, which killed five of the organization’s members. The only good thing about it was that it made many Italians more sympathetic to groups like O’Flaherty’s. The help was needed. Curfew was now 5:30 p.m. and public transportation had almost completely broken down. Koch’s ‘police force’ roamed the streets, shooting first and asking questions later. In April, Kappler got a hold of the teenage son of one of the padrones and handed him over to Koch. After torture, the boy revealed many of the organization’s hideouts, and every refugee in them was taken. By now, some 40 of the escapers had been recaptured and eight others shot. But the Allies were pushing at the Gustav line south of Rome. It was only a matter of time before they reached the city. Even the Germans knew that.

March also saw the massacre at the Ardeatine Caves, which killed five of the organization’s members. The only good thing about it was that it made many Italians more sympathetic to groups like O’Flaherty’s. The help was needed. Curfew was now 5:30 p.m. and public transportation had almost completely broken down. Koch’s ‘police force’ roamed the streets, shooting first and asking questions later. In April, Kappler got a hold of the teenage son of one of the padrones and handed him over to Koch. After torture, the boy revealed many of the organization’s hideouts, and every refugee in them was taken. By now, some 40 of the escapers had been recaptured and eight others shot. But the Allies were pushing at the Gustav line south of Rome. It was only a matter of time before they reached the city. Even the Germans knew that.

March also saw the massacre at the Ardeatine Caves, which killed five of the organization’s members. The only good thing about it was that it made many Italians more sympathetic to groups like O’Flaherty’s. The help was needed. Curfew was now 5:30 p.m. and public transportation had almost completely broken down. Koch’s ‘police force’ roamed the streets, shooting first and asking questions later. In April, Kappler got a hold of the teenage son of one of the padrones and handed him over to Koch. After torture, the boy revealed many of the organization’s hideouts, and every refugee in them was taken. By now, some 40 of the escapers had been recaptured and eight others shot. But the Allies were pushing at the Gustav line south of Rome. It was only a matter of time before they reached the city. Even the Germans knew that.

March also saw the massacre at the Ardeatine Caves, which killed five of the organization’s members. The only good thing about it was that it made many Italians more sympathetic to groups like O’Flaherty’s. The help was needed. Curfew was now 5:30 p.m. and public transportation had almost completely broken down. Koch’s ‘police force’ roamed the streets, shooting first and asking questions later. In April, Kappler got a hold of the teenage son of one of the padrones and handed him over to Koch. After torture, the boy revealed many of the organization’s hideouts, and every refugee in them was taken. By now, some 40 of the escapers had been recaptured and eight others shot. But the Allies were pushing at the Gustav line south of Rome. It was only a matter of time before they reached the city. Even the Germans knew that.

As Christmas 1943 approached, Major Simpson remembered seeing O’Flaherty’s room “crammed with small parcels, all wrapped in gaily colored paper and tied with red silk ribbons.” Molly Stanley had prepared these packages for the refugees, and O’Flaherty was rallying his fellow priests to help deliver them. The escapees and their hosts were likewise determined that Christmas would be as merry as they could make it. Mrs. Chevalier cooked an epic feast. Delia Murphy gave many impromptu concerts. But on December 27, the “fearful days” began.

As Christmas 1943 approached, Major Simpson remembered seeing O’Flaherty’s room “crammed with small parcels, all wrapped in gaily colored paper and tied with red silk ribbons.” Molly Stanley had prepared these packages for the refugees, and O’Flaherty was rallying his fellow priests to help deliver them. The escapees and their hosts were likewise determined that Christmas would be as merry as they could make it. Mrs. Chevalier cooked an epic feast. Delia Murphy gave many impromptu concerts. But on December 27, the “fearful days” began.